As much as I do love classic holiday movies, from the actual classics like White Christmas to fresher fan faves, a la Elf, I did feel inspired this year to seek out something new on the screen to celebrate the season.

For some reason, the new release, The Man Who Invented Christmas, based on Les Standiford’s The Man Who Invented Christmas – How Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits, didn’t make much of a splash in my neck of the woods. Whether limited in distribution or because of my failure to snag a ticket before it left theaters, when I finally decided to see it, piqued by its hint at creative marketing, my only choice would have been to drive to a small town in Massachusetts nearly two hours away from my office. Bah humbug.

So, I bought the book – which is what I normally insist on doing before checking out its reflection on the silver screen.

Here’s the gist of the story and a few reasons why I think it’s meaningful to today’s marketers…

The Scene

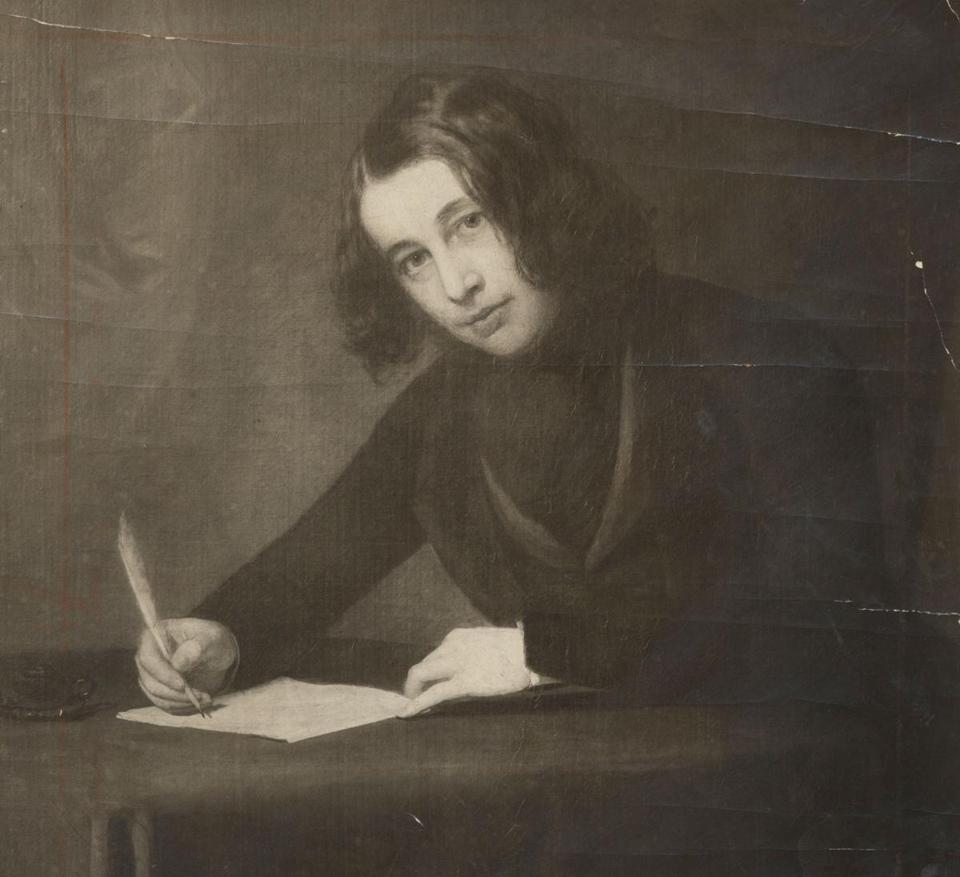

Christmas was NBD when Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol in 1843. You read that right. Christmas was barely celebrated and Dickens himself had to publish his own manuscript. Well, he had to foot the bill.

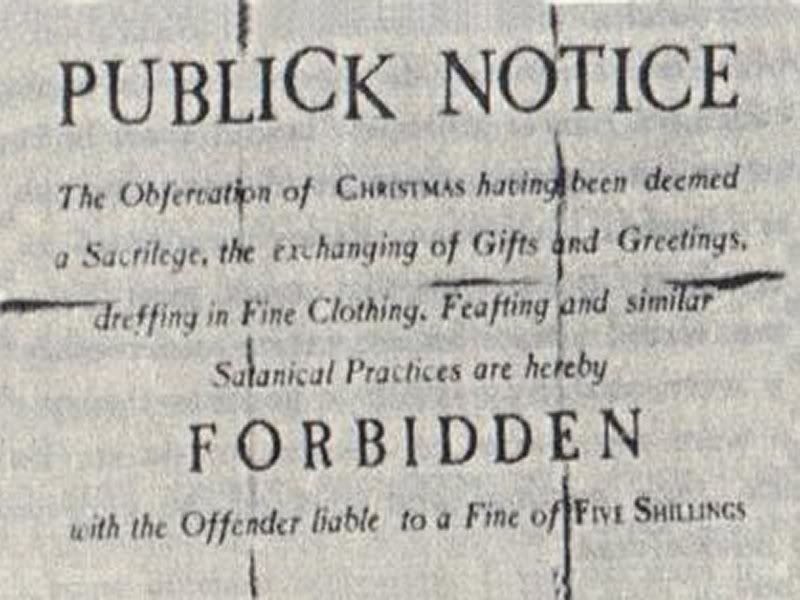

Let’s break this down… Why was Christmas barely a shadow of the celebration it is today? According to Standiford’s research, “In the eyes of the relatively enlightened Anglican Church, moreover, the entire enterprise of celebrating Christmas smacked vaguely of paganism, and were there Puritans still around, acknowledging the holiday might have landed one in the stocks.”

Charming.

Standiford goes on to explain that, “Part of the reason that Puritans found the holiday such anathema lies in the holiday’s roots in pagan celebrations that date back to Roman times. There is, in fact, no reference in the Christian gospels to the birth of Jesus taking place on the twenty-fifth of December, or in any specific month at all.”

Apparently, climatologists have even questioned the date because it gets mighty cold in the desert that time of year and it would be a brave or dense shepherd who sent his flocks to graze in below-freezing conditions.

So. Christmas was problematic for a variety of reasons – read the book, seriously, it’s fascinating. Despite all the research, the book doesn’t dare a dry moment; instead, reading more like a conversation with a very wise and approachable historian, who will be patient with your rather limited historical scope.

Moving on to why Dickens had to shell out his own coin (and he didn’t have much of it) in hopes that the “little carol” would shine light upon coal-dusted London.

Confronted by less than desirable terms presented by his publisher, Dickens managed to preserve his working relationship with them, provided they publish the book, according to his wishes (in other words, not be cheapos about it). Upon their consent, he would cover publishing costs.

Standiford captures the modern-day version of this scenario with his observation, “In contemporary terms, then, A Christmas Carol was to be an exercise in vanity publishing.”

Just in time for Christmas, and after concentrated effort on the part of Dickens, his publishers, and the printers, 6.000 copies of A Christmas Carol were released on December 19 – a move that would prove a real gamechanger to Dicken’s career… and to a greater appreciation of Christmas.

Behind Said Scene

What is so extraordinary about Dicken’s decision to assume his own publishing costs comes from the simple fact that the man was broke, like brand-new-business-owner broke. As my dear friend’s father – himself a business owner – would say, Dickens had “a case of the shorts.”

Perhaps even more stressful than a serious lack of shillings is a different kind of security, namely insecurity. Or, in Dickens’ case, significant doubt – not so much in himself, but in the market. Standiford states, “…despite his own confidence in the power of his tale, Dickens had at least two good reasons to be apprehensive as publication day for his story approached. One had to do with the nature of the holiday itself, and the other with the dire financial straits he found himself in.”

In other words, Dickens knew he had the goods. He just couldn’t be sure of their delivery. But, by believing in what he had created, he created his consumer. Not unlike Steve Jobs… “A lot of times people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

How did Dickens know what his readers wanted?

He tapped into what he wanted.

The Message was Authentic to its Voice

You can’t honestly believe in a product or a service if, given the chance, funds, or whatever it takes, you wouldn’t purchase or solicit it yourself. Part of A Christmas Carol’s success can be attributed to its author’s authentic voice.

If in real life, Dickens was more Scrooge than Tiny Tim, the book might not have given Christmas its due or delivered Dickens out of debt. As Standiford explains, “The concept for A Christmas Carol…did not come to its author out of nowhere, for Dickens had always been greatly enamored of the holiday…While the words are attributed to a character in a novel, there is little doubt that the sentiments are those of the author.”

Dickens established trust with his readers via his well-rendered characters and the honest dialogue between them. From that trust, Dickens could broadcast his message, static-free.

An Unbroken Connection over an Unfulfilled Need

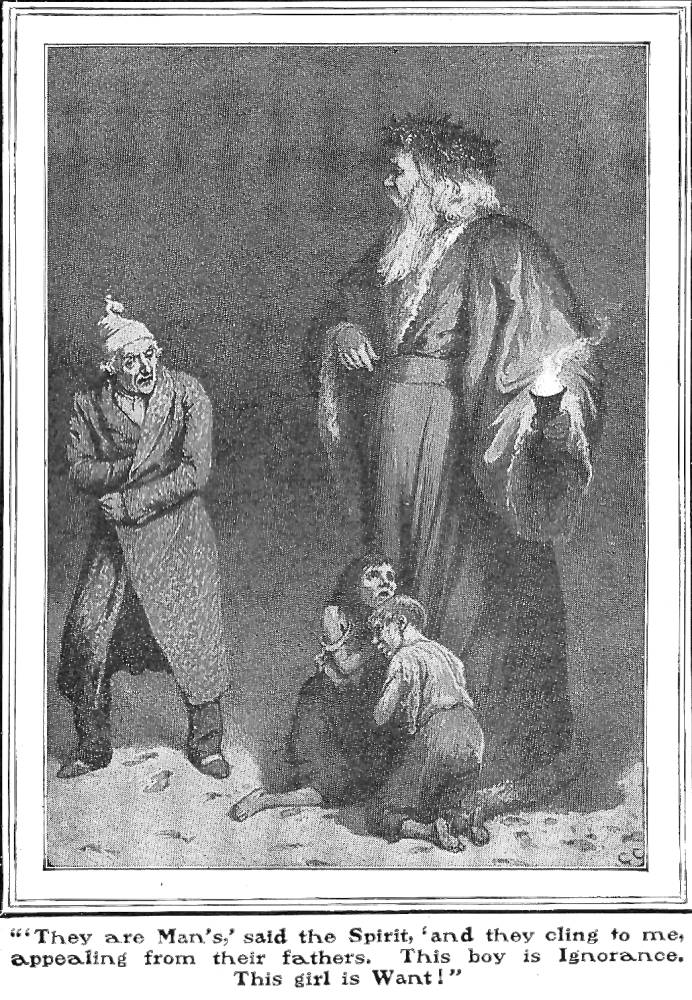

Ultimately, A Christmas Carol is Dickens’ call to action. A two-pronged call to action, to be exact. The first: Eliminate Ignorance; the second: Eliminate Want.

While aims have been made, certainly since the Industrial Revolution, this mission continues to miss its mark. Ignorance and Want are alive and well, perhaps even thriving in certain areas and among certain audiences. So, the call to action persists and Dickens’ connection with his audience remains unbroken.

A blessing and a curse, no doubt, but no matter your beliefs, A Christmas Carol is certainly a tale worthy of consideration by today’s marketers, entrepreneurs, and anyone eager to create something that might be cause for celebration.